From a very young age, Eugene Istomin remained torn between his mother’s Judaism and his father’s Orthodox religion, even though neither of them practiced their religions. His reaction was to distance himself from both, and he refused to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah. Later on, he would read and research widely on all the different religions, becoming closer to Catholicism after meeting Marta. His faith in humanity and in God did not need to follow the path of one religion. His father had given him the model for this freedom; he had chosen to be buried in the Glendale Jewish Cemetery in Queens, where he knew that his wife would one day come to join him. For his part, Istomin decided to be buried in the Christian Cemetery in El Vendrell, not far from the grave of Casals, so that Marta would be able to rest close to the two men with whom she had shared her life.

This distance from the Jewish religion in no way prevented Istomin from feeling profoundly attached to Israel. He had infinite admiration for the Israeli people, their courage both at work and in war, their intelligence, and their culture. He said that he would willingly give his life for Israel, and he participated in a great number of benefit concerts for various causes linked to Israel. He went there almost every year to give master classes. He generously welcomed and helped young Israeli musicians coming to the United States, both through talents he had identified (such as Yefim Bronfman), or those who Stern sent to him like Pinchas Zukerman and Shlomo Mintz. He even agreed to take part in concerts presenting works of contemporary Israeli composers.

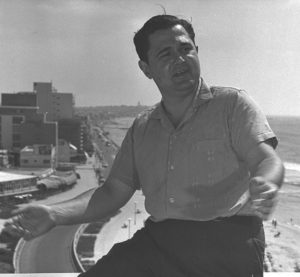

When Istomin was asked which country had the best audiences, he was always very cautious in his replies, not wanting to appear like a populist by naming the country that he was in at the time, and yet anxious not to upset his hosts either! However, it was clear that he had a preference for Israeli audiences: he acknowledged that nowhere else could such fervor and expertise be found. He gave his first concerts in Israel in 1961, as part of the first Israel Festival, which at that time was solely a musical event. It was there that the Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio’s adventure really took flight. Istomin also played with the Budapest Quartet. On the 29th of September, 1961, Time Magazine described the festival in the following terms: “Casals’ mesmerizing performances and eerily effective rendition of Beethoven’s Trio in D Major (the ‘Ghost Trio’) by Violinist Isaac Stern, Pianist Eugene Istomin and Cellist Leonard Rose were the high points of Israel’s month long festival. But there were other triumphs. Staged at seven sites from Haifa to the Revivim kibbutz, the festival drew 56,000 people to 23 concerts. In Tel Aviv, 500 music lovers who could not squeeze into the already 3,000-seat Mann Auditorium were chased by police…”

Istomin often returned to play at the Israel Festival, with his colleagues of the Trio, the Budapest Quartet, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and the Youth Orchestra, in 1963, 1967, 1970 and 1973. In 1973, all the musicians, including Casals, inaugurated the Jerusalem Music Centre in Mishkanat Sha’ananim. This was an initiative led by Isaac Stern, who wanted the world’s greatest musicians to be able to come to Israel to collaborate with Israeli teachers and give lessons to the country’s most talented young musicians. It was Teddy Kolleck, the mayor of Jerusalem, who was considered by Sasha Schneider to be the only person in Israel who understood the importance of the arts for the development and communication of the country, who oversaw its progress and completion. Istomin only gave two major concert series with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as a few scattered concerts, and he was saddened that Mehta no longer invited him after becoming its musical director.

Politically speaking, Istomin’s position was clear. He was fiercely attached to the Israeli land and people, and followed the wars of 1967 and 1973 with deep concern, and then relief. He was convinced that it was certainly necessary to respond with force when there was no other solution, but that negotiation was the only way to securing a lasting peace, and that the only possible future for Israel was to coexist in harmony with its neighbors. Istomin kept and treasured the article written by his friend Eugenie Anderson in 1971, who at that time was a United Nations delegate: “My dominant impression from my stay in Israel is that the Israelis want peace with security – not peace at any price. They are determined that this time they will return only to secure, recognized, agreed boundaries. This means that new borders must be negotiated.”

Isaac Stern, Leonard Rose, Golda Meir, Eugene Istomin, Alexander Schneider, David Ben-Gurion on the left. Pablo and Marta Casals on the right. 1973

Istomin’s friends in Israel were members of the Labour Party, dedicated to the country’s grand ideals: David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, and particularly Teddy Kolleck and Itzhak Rabin, to whom Istomin was very close, and whose assassination drove him to despair. These were visionary people who were prepared to engage in military operations when necessary, but who also aspired to a negotiated peace and peaceful cohabitation with Arab countries and the Palestinians. In addition, they held a profound belief in social progress and in culture.

Menahem Begin, who became Prime Minister after the 1977 elections, had been their staunchest opponent. To the surprise of many, he turned out to be a man of peace: the negotiator of the Camp David Accords in September 1978 (accompanied by Moshe Dayan, former Labor minister, who had become his Foreign Minister); and then the signatory of the peace treaty with Egypt, the first that Israel would ever sign with an Arab country. Israel returned the Sinai territories conquered during the Six-Day War and obtained a promise for the autonomy of the West Bank and Gaza territories. Egypt recognized the existence of Israel and the two countries committed themselves to normalizing their diplomatic relations and certain free movement agreements. The United States acted as witness to the accords and helped Israel to move its Sinai military bases to Negev. The treaty was signed by Menahem Begin and Anwar Sadat on the 26th of March, 1979, in Washington, DC, in the presence of President Carter, who had been the orchestrator of this spectacular reconciliation.

Istomin felt very happy about this first great step towards peace and serenity. As luck would have it, his touring calendar had him visiting Jerusalem on the invitation of its mayor, Teddy Kollek, to give two concerts for the opening of the Jerusalem Spring Festival on the 1st and 2nd of May: a recital and a performance of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto with the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. This concert was to be televised to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Israel’s admission to the United Nations. Istomin was also due to give a series of master classes in Mishkenot Sha’ananim the week before, when the idea occurred to him of celebrating the newly signed peace agreement by proposing to the Egyptians that he come and play for them before heading to Israel.

Istomin felt very happy about this first great step towards peace and serenity. As luck would have it, his touring calendar had him visiting Jerusalem on the invitation of its mayor, Teddy Kollek, to give two concerts for the opening of the Jerusalem Spring Festival on the 1st and 2nd of May: a recital and a performance of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto with the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. This concert was to be televised to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Israel’s admission to the United Nations. Istomin was also due to give a series of master classes in Mishkenot Sha’ananim the week before, when the idea occurred to him of celebrating the newly signed peace agreement by proposing to the Egyptians that he come and play for them before heading to Israel.

The State Department rapidly agreed to this and Istomin arrived in Cairo on the 18th of April. His arrival made headlines in the Egyptian press. He arrived at just the right time to make the new spirit of political and cultural openness a reality. In the space of four days, he met the teachers of the Cairo Conservatory, gave two master classes, performed a recital and was even able to make a detour to see the pyramids. His welcome was more than warm, and he admitted to being pleasantly surprised by the high level displayed by the students. On the 22nd of April, as a way of thanking him and of celebrating the newly established peace, the Egyptian government authorized Istomin to travel directly from Cairo to Jerusalem, granting him an unprecedented first-ever visa!

Istomin’s arrival in Jerusalem was just as triumphant, in the euphoria of establishing the first ever-links with an Arab country. His two concerts earned him endless applause, and five days later he found himself back on stage at Carnegie Hall, playing the ‘Emperor Concerto’ once again, this time with the American Symphony Orchestra. Symbolically, he was also bringing together the three actors in this historic reconciliation: Cairo, Jerusalem, and New York: this too was an historic first!

Istomin wrote straight away to Walter Mondale, the current Vice-President of the United States, with whom he had maintained a friendship ever since supporting Hubert Humphrey together, and told him about a project that he had dreamed up while giving master classes at the Cairo Conservatory. He said that he felt convinced that he could persuade the Egyptians to participate in an exchange program which would allow Egyptian piano students to study in Jerusalem with outstanding professors. Istomin emphasized that such an initiative would be simple to put into place and that it would have a powerful symbolic impact, all the more so as he had the support of Teddy Kolleck, and he subsequently asked Mondale to speak about it with President Carter. Mondale, who was always very attentive to cultural affairs, did what he could, but the project remained stuck in the mire of diplomatic and administrative circuits.

Istomin was disappointed by the limited response that his project garnered. The State Department made no effort to enhance the event that had left such an impact on the Egyptians and Israelis. Istomin was not so much sorry about this for his own sake, but for that of the clearly recurrent absence of music and culture in the American government’s political strategies, when once again, he had just shown that nothing was more effective for bringing people together!

Istomin would try again in the following years to establish regular exchanges between Israeli and Egyptian musicians, but in vain. His strongest media support was from Pierre Salinger, who was the Paris correspondent for ABC at the time, and who had sent a team to film Istomin in Cairo and Jerusalem. Unfortunately, the feature that he had prepared was not broadcast in America because of another breaking international crisis that interrupted regular news programming. The written press was satisfied with only a few lines, except for Musical America, which interviewed Istomin and devoted two pages to the event. .

Eugene Istomin proved to be a precursor of things to come, twenty years before Daniel Barenboïm and the birth of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. Istomin had attempted to give music its natural role as a source of mutual understanding between peoples. He had also attempted, in 1978, to contribute to changing mindsets. Istomin, who had just recently agreed to play in Germany, was taken on as a soloist with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra for a series of concerts conducted by Klaus Tennstedt. This was the first time that a German conductor had ever been invited to conduct the Israel Philharmonic, and the reaction of some of the musicians, journalists and public was very negative, even violent. Istomin tried his best to calm down the opponents and to convince them that the time for hate and rejection was over. Perhaps his strong support of a German conductor was also the reason why some people were opposed to Istomin being invited again by the Israel Philharmonic. .

Despite his love for and devotion to Israel, Istomin kept a certain distance from the Jewish community. While he made himself available to stand up for any causes that seemed worthy to him without expecting anything in return, he maintained a principal of never confining himself to fixed identities, and shied away from seeking out the help of groups that he belonged to, whether it be the Russian diaspora or the Democratic political family, whom he was close to for so long.

Concerts

1961 Israel Festival

August 29. Jerusalem. Mozart, Piano Quartet K. 478; Dvorak, Piano Quintet Op. 81, with the Budapest Quartet.

September 3, 6 & 9. Beethoven, Trio Op. 70 No. 2; Ravel, Trio ; Mendelssohn, Trio No. 1 Op. 49, with Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose.

September 7. Haifa. Brahms, Trio No. 2 Op. 87; Beethoven, Trio Op. 70 No. 1; Schubert, Trio in B flat Major, with Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose.

On September 18, for the closing concert, Istomin was scheduled to play Mozart’s Concerto for Two Pianos with Rudolf Serkin and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Alexander Schneider, but he was forced to cancel, due to tendonitis in his thumb.

1970 Israel Festival (with Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose)

August 15. Jerusalem. Beethoven, Cello Sonata Op. 5 No. 1; Violin Sonata Op. 30 No. 1; Trio Op. 97 “Archduke”.

August 17. Caesara. Beethoven, Trio Op. 1 No. 3; Violin Sonata No. 8; Cello Variations on “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen”; Trio Op. 70 No. 1.

August 20 & 22. Caesara and Jerusalem. Beethoven, Triple Concerto Op. 56. Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Alexander Schneider.

Other dates and programs to be found.

1973 Israel Festival

Beethoven, Trio Op. 70 No. 2; Brahms, Trio No. 3 Op. 101; Mozart, Piano Quartet K. 478, with Isaac Stern, Alexander Schneider (viola) and Leonard Rose.

Mozart, Concerto No. 9 K. 271. Youth Festival Orchestra, Alexander Schneider.

With the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

1963, May 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25 ,27 & 30. Tel-Aviv and Haïfa. Schumann, Concerto. Zubin Mehta.

1963, May 29. Tel-Aviv. Beethoven, Concerto No. 4. Zubin Mehta.

1967, July 22. Tel-Aviv. Brahms, Concerto No. 2. Josef Krips.

1978 October 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31. Tel-Aviv and Jerusalem. Beethoven, Concerto No. 4. Klaus Tennstedt.